A Queen on the Nile: Revisiting Elizabeth II’s 1954 Visit to a Changing Uganda

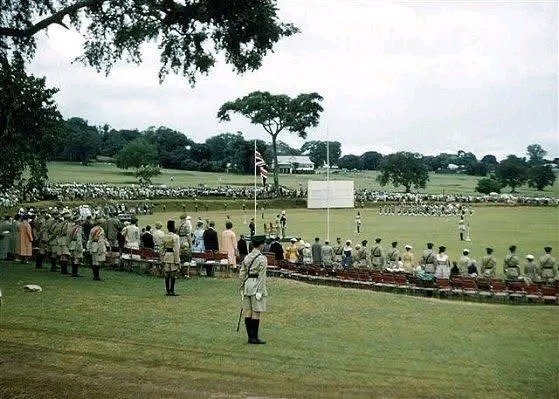

Jinja, 1954. The air hummed not only with the latent power of the Nile but with a palpable sense of occasion. Queen Elizabeth II, a young monarch of a vast empire, had set foot on Ugandan soil. Her arrival marked a moment of profound symbolism, capturing an empire in transition and a protectorate on the cusp of a new destiny.

The official reception was a study in this complex dynamic. The Queen was received by Kyabazinga Sir William Wilberforce Nadiope, the leader of the Busoga kingdom, whose presence alongside the British Crown illustrated the intricate layers of authority within the colonial structure. Uganda was still a British Protectorate, but the winds of self-rule, which would indeed blow into independence less than a decade later, were already gathering force.

The primary purpose of the Queen’s visit was both political and ceremonial: to commission the Owen Falls Dam in Jinja. This monumental hydroelectric project was presented as a beacon of colonial modernization, a concrete testament to Britain’s imperial footprint on the world’s longest river. It promised to harness the mighty Nile, a source of life and legend, for economic progress. (The dam would later be renamed the Nalubaale Power Station, reclaiming its identity with an indigenous name meaning “Goddess of the Lake”).

The event was staged with grand pageantry. Jinja, the industrial heart of Uganda, was transformed into a royal stage. Crowds thronged the roadsides, flags—both Union Jacks and local banners—fluttered in the breeze, and the rhythmic echo of drums provided a soundscape for the historic day. Local chiefs and dignitaries adorned their finest regalia, with the Basoga people, on whose land this monumental project stood, placed at the very center of the spectacle. This was not merely a state visit; it was the Queen coming to Busoga itself, to stand at the very source of the Nile where it begins its epic journey north.

Adding to the profound symbolism of the day was the presence of other Ugandan traditional leaders, most notably Sir Edward Mutesa II, the Kabaka of Buganda. His attendance was highly significant, embodying the delicate and often tense balance of power between the British Crown and Uganda’s powerful indigenous monarchies. For the ordinary Ugandans who witnessed the event, the sight of the Queen and the Kabaka together was extraordinary, almost surreal. It was a vivid convergence of two worlds: one imperial and foreign, the other deeply African and familiar.

The 1954 visit remains a poignant snapshot in history. It was a moment where the old order, represented by the commissioning of a colonial dam, shared the stage with the emerging future of Ugandan self-determination, symbolized by the proud presence of its own kings. The Queen’s walk on Ugandan soil was a step across a threshold, marking the beginning of the end of one era and the uncertain dawn of another.