Scholar Mamdani Argues Museveni’s “Slow Poison” Has Harmed Uganda More Than Amin’s Brutality

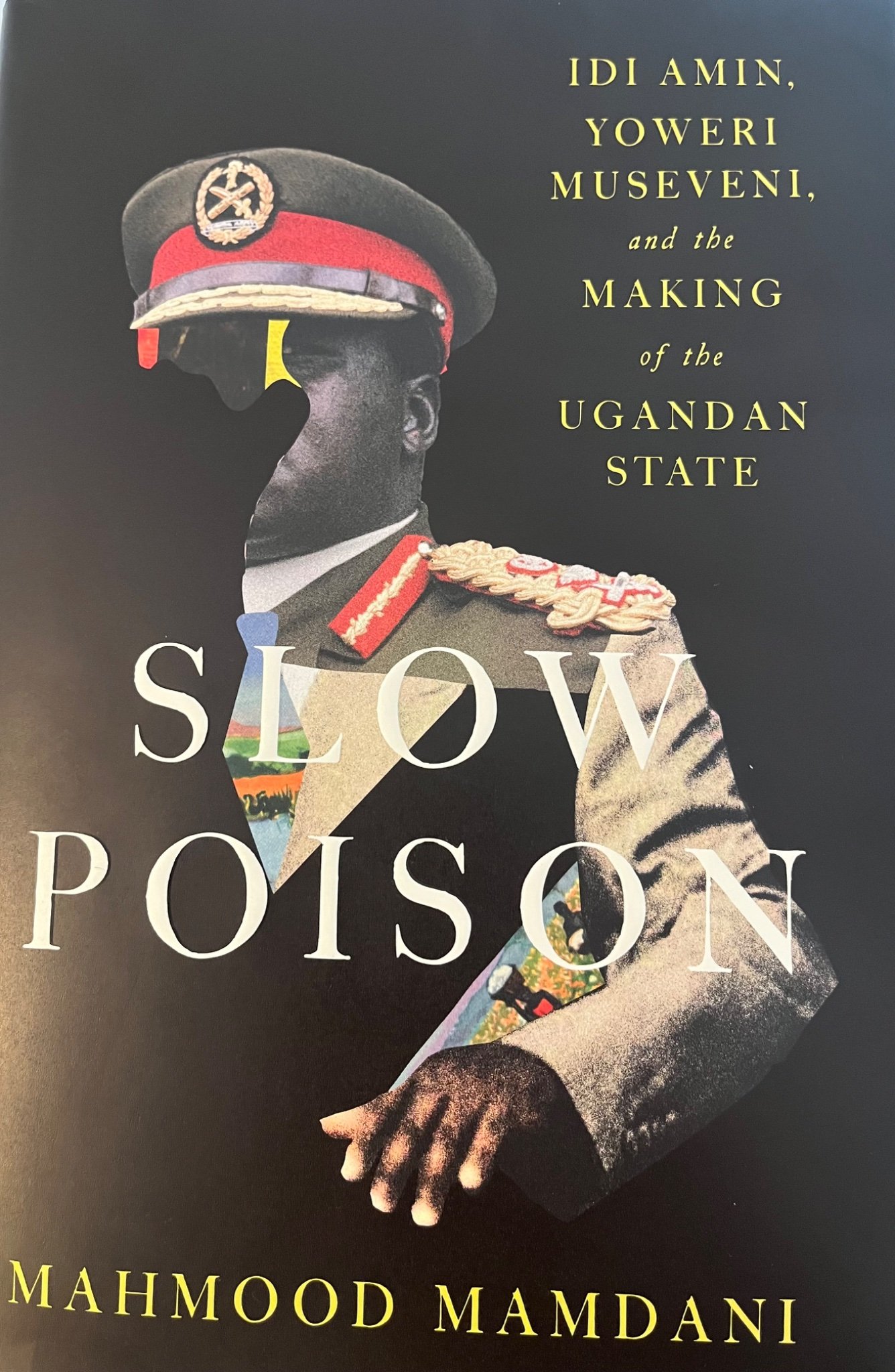

Acclaimed Ugandan academic Mahmood Mamdani has sparked international debate with his new book, “Slow Poison: Idi Amin, Yoweri Museveni, and the Making of the Ugandan State,” which contends that President Yoweri Museveni’s four-decade rule has inflicted deeper, more structural damage on Uganda than the overt brutality of Idi Amin.

Published by Harvard University Press, the book draws on Mamdani’s personal experiences and historical analysis to portray both leaders as products of British colonial “divide and rule” tactics. While Amin’s regime was characterized by rapid and overt violence, Mamdani introduces the concept of “slow poison” to describe Museveni’s subtler authoritarianism, which he argues has turned citizens into clients of a state that rules through ethnic fragmentation, violence, and corruption.

The book has ignited a firestorm of reaction on social media platform X. Uganda’s Permanent Representative to the UN, Adonia Ayebare, publicly criticized the work, while prominent journalists and activists like Charles Onyango-Obbo and Nicholas Opiyo have praised it.

Beyond its specific focus on Uganda, the book is being interpreted as an indirect critique of contemporary progressive dogmas surrounding identity. As commentator Geoff Shullenberger noted in a thread on X, Mamdani’s analysis challenges frameworks that center on “indigeneity” versus “settler.”

Mamdani’s work, as highlighted in a passage from the book, explains how the National Resistance Army (NRA), once in power, reversed its initial strategy of building a majority around common grievances. Instead, it began to maintain power by “disrupt[ing] the development of an interest-bound majority by mobilizing identity-based minorities.” This strategy, the book argues, diffuses opposition and stabilizes power through continued fragmentation.

The central lesson, resonating beyond Uganda, is that the “indigenous/settler” binary is not an anti-colonial framework but a colonial one. British authorities defined and reinforced tribal identities to parcel the population into manageable categories, making it difficult for a unified democratic citizenry to emerge. Mamdani’s critique extends to modern identity politics and even state-mobilized feminism, which he frames as a continuation of this colonial logic, forestalling the constitution of a cohesive democratic body.

“Slow Poison” thus positions Uganda’s post-colonial trajectory as a cautionary tale about how the tools of colonial control can be perpetuated by independent states, with consequences that are profound and lasting.