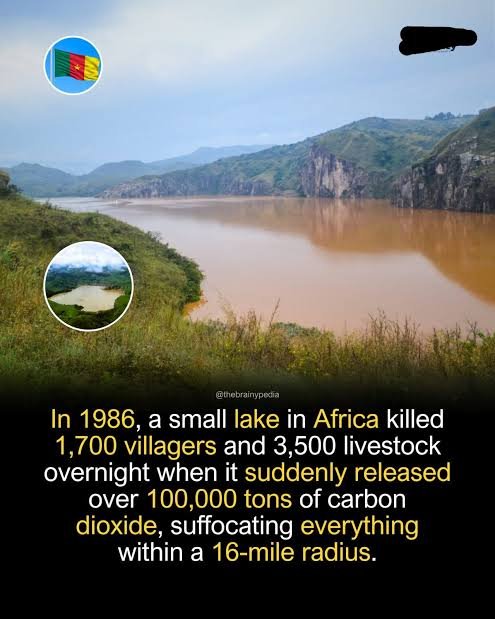

The Silent Killer: Revisiting the Lake Nyos Limnic Eruption, 38 Years On

CAMEROON, NORTHWEST REGION — In the quiet pre-dawn hours of August 21, 1986, one of the rarest and most tragic natural disasters in modern history unfolded at Lake Nyos. A volcanic crater lake in the verdant highlands of northwestern Cameroon silently released a deadly, invisible force that claimed thousands of lives, leaving behind a haunting landscape of silent villages and a profound scientific mystery.

A Night of Silent Death

Residents of the villages surrounding the lake—primarily Nyos, Cha, and Subum—went to sleep as usual. Without warning, a massive cloud of carbon dioxide (CO₂), heavier than air, erupted from the lake’s depths, spilling over the crater rim and pouring into adjacent valleys. The gas displaced breathable air, creating a suffocating blanket over an area roughly 25 kilometers across.

Victims, including an estimated 1,746 people and approximately 3,500 livestock, died rapidly from asphyxiation in their sleep. The eerie scene discovered by first responders and survivors from higher ground was one of undisturbed stillness—bodies lay as if peacefully resting, with no signs of struggle, next to perished wildlife. The vegetation, unharmed by the inert gas, added to the surreal and chilling aftermath.

The Science of a “Lake Explosion”

Scientists later classified the event as a limnic eruption—a sudden release of dissolved gases from a deep lake. The investigation revealed a perfect storm of conditions:

- Gas Accumulation: Lake Nyos, a deep volcanic crater, sits atop a magma chamber. For centuries, CO₂ seeped from below, dissolving under immense pressure in the cold, deep waters, like carbonation in a sealed soda bottle.

- The Trigger: The precise catalyst for the 1986 event remains debated. A landslide, small earthquake, or even a weather event may have disrupted the lake’s stable layers, causing the gas-saturated bottom water to rise rapidly.

- The Eruption: As the water ascended, the pressure dropped catastrophically, triggering a runaway process where the CO₂ bubbled out of solution. This created a powerful fountain, ejecting water over 80 meters high and releasing an estimated 1.24 million tonnes of CO₂ into the atmosphere in roughly 20 minutes.

Aftermath and a Pioneering Solution

The Lake Nyos disaster, along with a smaller similar event at Lake Monoun in 1984, alerted the world to a previously unrecognized natural hazard. It prompted an urgent international response focused on two questions: what caused it, and how could it be prevented from happening again?

Scientists realized the lake was actively recharging with CO₂, posing a continuous threat. In a landmark feat of environmental engineering, an international team led by French and Cameroonian scientists installed the world’s first degassing pipe in Lake Nyos in 2001.

Operating like a giant soda straw, the pipe siphons CO₂-rich water from the bottom of the lake. As the water rises, the pressure decreases, allowing the gas to bubble out safely at a controlled rate before the water is returned to the lake. Multiple pipes have since been installed, significantly reducing the gas saturation to safe levels. Continuous monitoring stations now keep vigilant watch over gas concentrations and seismic activity.

A Lasting Legacy

Today, Lake Nyos stands as both a memorial and a testament to scientific ingenuity. The degassing columns, constantly bubbling, are a visible reminder of the hidden danger below and the ongoing effort to neutralize it. The disaster underscored the interconnectedness of geology, limnology, and public safety, transforming disaster preparedness for volcanic lakes worldwide.

While the scars on the landscape and the communities endure, the proactive measures ensure that the silent killer of 1986 has been, hopefully, permanently subdued. The legacy of Lake Nyos is a powerful reminder of nature’s hidden forces and humanity’s capacity to understand and mitigate them.